Literature Review on Intervention Methods for Youth Offenders

Abstract

Youth offending is a problem worldwide. Young people in the criminal justice organisation have frequently experienced adverse childhood circumstances, mental health bug, difficulties regulating emotions and poor quality of life. Mindfulness-based interventions can help people manage problems resulting from these experiences, but their usefulness for youth offending populations is not articulate. This review evaluated existing evidence for mindfulness-based interventions among such populations. To be included, each report used an intervention with at least one of the iii core components of mindfulness-based stress reduction (breath sensation, body awareness, mindful move) that was delivered to young people in prison or community rehabilitation programs. No restrictions were placed on methods used. 13 studies were included: three randomized controlled trials, one controlled trial, three pre-mail report designs, three mixed-methods approaches and three qualitative studies. Pooled numbers (north = 842) comprised 99% males aged between xiv and 23. Interventions varied so it was not possible to identify an optimal approach in terms of content, dose or intensity. Studies found some comeback in diverse measures of mental health, self-regulation, problematic behaviour, substance use, quality of life and criminal propensity. In those studies measuring mindfulness, changes did not accomplish statistical significance. Qualitative studies reported participants feeling less stressed, better able to concentrate, manage emotions and behaviour, improved social skills and that the interventions were acceptable. Generally low written report quality limits the generalizability of these findings. Greater clarity on intervention components and robust mixed-methods evaluation would meliorate clarity of reporting and amend guide hereafter youth offending prevention programs.

Introduction

Many countries around the earth place a high priority on the rehabilitation of young people who offend. This group is typically characterized by socio-economic impecuniousness, adverse babyhood experiences (ACEs), low educational attainment, difficulties with regulating emotions and behaviour, poor mental health and impaired quality of life (QOL) (Dodge and Pettit 2003; Ou and Reynolds 2010). A growing trunk of evidence suggests that such factors contribute to delayed maturational evolution and dumb social skills (Monahan et al. 2009, 2013) and have detrimental effects on neural development in encephalon areas thought important in executing the cognitive control required for regulating emotions (Abram et al. 2004). Difficulties with regulating emotions and behaviour, poor cerebral abilities and coping skills and poor mental wellness have all been postulated as important determinants of subsequent offending behaviour amidst young people. The "What Works" report on factors that may reduce re-offending suggests that offenders are more than likely "to desist from offending if they manage to learn a sense of control over their own lives and a more positive outlook on their future prospects" (Sapouna et al. 2011, p. 24). The report suggests that interventions aimed at enhancing coping skills and psychological resilience are most likely to reduce re-offending.

Clearly, the prevention of youth offending by tackling the wider social determinants of health is a much needed upstream solution, which depends on political and societal responses to inequalities (Marmot 2005), but interventions at a group or individual level are also needed to help those currently affected. These young people stand for a particularly vulnerable grouping, and effective interventions are needed to help them manage stress and amend cerebral and emotional skills. Currently, the near researched interventions for those in custody are based on cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) principles (Andrews et al. 1990; Lipsey 1995; Lösel 1995). Although CBT has strong empirical bankroll, the evidence remains limited in this specific population and it is recognized that this approach may need supplementation (Sapouna et al. 2011; Ward et al. 2012; Wilson and Yates 2009). Recently, increasing attention has been placed on natural protective factors, private strengths and positive treatment alliances (Ward et al. 2012). One such approach that may be useful in this regard is mindfulness.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs), derived from Buddhist meditation practices and secularized for apply in contemporary order, preferentially train attentional sensation, enhancing emotional and behavioural regulatory skills and generating a shift in ane's perspective of self (Hölzel et al. 2011). MBIs have a growing evidence base for utilize within clinical and not-clinical settings alike, improving both psychological operation and wellbeing in people with chronic health problems (Bohlmeijer et al. 2010; Fjorback et al. 2011; Goyal et al. 2014; Mars and Abbey 2010). Systematic reviews, meta-analyses and randomized controlled trials (RCTs) suggest that MBIs may be potentially useful in numerous relevant domains, including the management of anxiety (Grossman et al. 2004; Hofmann et al. 2010), stress (Chiesa and Serretti 2009), depression (Baer 2003; Kuyken et al. 2008; Teasdale et al. 2002), trauma (Kuyken et al. 2015) and addictive behaviours and substance misuse (Witkiewitz et al. 2005, 2013). Further, those studies that accept included active comparator groups suggest that, in general, MBIs are as effective at improving mental health and wellbeing as other commonly used interventions in this context, such as CBT or antidepressants (Goyal et al. 2014; Kuyken et al. 2015). In addition, systematic review evidence suggests beneficial effects from manualized MBIs on retentivity, some aspects of executive office (inhibition and set shifting), cognitive flexibility and meta-awareness (Lao et al. 2016). Based on this evidence, there are several reasons to hypothesize why mindfulness may have particular relevance for young offenders.

A number of studies accept demonstrated an clan betwixt youth offending and the ability to self-regulate emotions, in detail impulsivity and impaired cognitive and behavioural flexibility (Chitsabesan et al., 2006; Fazel et al. 2008; Vitacco et al. 2002, 2010). Ability to regulate emotions requires constructive executive functioning, that is, the power to inhibit inappropriate behaviour (inhibitory control), activate an advisable response (activation control) and shift and focus attention as required (effortful command) and to integrate information, plan, detect error and modify behaviour as necessary (Rothbart 2007; Rothbart et al. 2007). Maturational brain changes betwixt adolescence and early adulthood may explain why some young people who offend early on seem to show decreases in impulsivity and improvements in self-command over time (Loeber et al. 2013). During this stage of maturation, run a risk perception is refined, resistance to peer influence strengthened, anticipation of time to come consequences improved and sensation seeking and impulsivity lessened (Steinberg 2007; Steinberg et al. 2008, 2009). For those not obviously showing such maturation and improvement, seeking to assist the developmental procedure through targeted intervention makes sense.

In addition, stress that is perceived as uncontrollable can rapidly impair operation on tasks requiring elevation-down, prefrontal cognitive control (Arnsten 1999; Cerqueira et al. 2007) and has also been shown to impair self-regulatory power in adolescents (Duckworth et al. 2013). Exposure to such stressors is thought to direct processing away from higher cerebral functioning, behaviours instead being driven by emotion-based systems associated with increased vigilance and scanning of the environment for the detection of potential threat. This may atomic number 82 to impairments in cocky-regulatory processing, where the individual has difficulty with the experiencing, interpreting, regulating and managing of emotional country(s) (DeBellis and Thomas 2003). It seems clear that youth offending populations represent a particularly vulnerable grouping, with a need for effective interventions that tin improve cognitive and emotional skills and the ability to manage stress.

Mindfulness meditation has been shown to strengthen neural pathways betwixt areas of the prefrontal cortex and limbic arrangement associated with regulating the stress response and emotional experience (Hölzel et al. 2011). Mindfulness training is proposed to provide the cognitive tools to deal more skillfully with mental reactions to stressors, and a primary outcome of enhanced mindfulness is the improved capacity for experiencing and tolerating negative affect and distressing emotional states, both common findings amongst offending populations (Witkiewitz et al. 2013). Thus, MBIs may serve to accost several key constructs underlying offending behaviours (Farrington 2000).

Every bit we movement towards testify-based practice in forensic psychology settings, such as young offenders' institutions, information technology is important to determine whether novel treatments such as MBIs exercise constitute potential rehabilitative options for young people involved with the criminal justice system. However, before undertaking farther master evaluations, it is necessary to take stock of existing research bear witness in this area. This will aid us make up one's mind what is already known and available in the literature base regarding the potential benefits of a MBI within youth offending populations. The electric current review has four objectives: (1) determine the types of studies that have been published regarding the use of MBIs within youth offending populations, (2) identify the population characteristics of the groups in which MBIs have been studied, (3) determine the specific types of intervention strategies that accept been used and (four) ascertain what outcomes have been assessed and what they have shown.

Method

Search Strategy

This scoping review followed the 5-stage approach advocated past Arskey and O'Malley (2005), incorporating the more contempo recommendations made by Levac et al. (2010). In Oct 2016, nine electronic bibliographic databases and information repositories (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, CINAHL, ASSIA, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, Web of Scientific discipline and Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED)) were searched forth with the ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database. Selected subject field headings were combined with cardinal words relating to mindfulness and offending to create a search strategy that was finalized for use in MEDLINE and modified as required for use in other databases, using Boolean operators, search symbols and controlled vocabulary. Hand searching of the reference lists of included papers for potentially relevant studies non identified by the database searches was also carried out. Studies were accounted relevant at this stage if the title included one or more of the agreed search terms.

Selection Criteria

Studies were selected for inclusion if (1) the intervention included at to the lowest degree one of the three principal techniques of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) (i.e. breath sensation, body awareness or mindful movement), as it most closely represents the standardized model; (2) the focus was on youth offending populations (incarcerated or being rehabilitated in the community); and (3) whatsoever discernable methods were used (either quantitative or qualitative) to assess main data.

Studies were excluded if they were non-human, written in a language other than English or published prior to 1980 (after which, MBSR beginning appeared in the published literature). No restrictions were placed on study design. However, all included studies had to incorporate primary data (i.due east. original research obtained through first hand investigation). Therefore, secondary data sources such as adept opinion papers were not included. No restrictions were in place with regard to study quality. Nevertheless, in the current review, each of the included studies was quality assessed to assist the reader when interpreting the findings.

Selection of Papers for Inclusion

Two reviewers (SS and RS) screened titles and abstracts using the inclusion/exclusion criteria to select potentially eligible papers. Copies of the full papers were obtained and authors contacted when necessary to determine whether the intervention met the inclusion criteria. Both reviewers independently read the full papers to determine if they met inclusion criteria. Whatsoever discrepancies were adjudicated over by a third, more than senior reviewer (SM).

Quality Appraisement

Quality appraisal was used to assess the quality of the literature (i.e. to make up one's mind whether each study was carried out correctly, in line with existing recommendations and standards). It was not intended to stratify papers into a hierarchy of testify (Daudt et al. 2013; Petticrew & Roberts, 2008). Papers were not excluded from the review on the basis of poor quality methods. For the qualitative studies, a quality appraisal tool based on Spencer et al. (2003) "framework for assessing qualitative evaluations" (FAQE) was used as an assist to provide informed judgment rather than a mechanistic arroyo. This framework consists of 18 open-ended questions, governed by four guiding principles: (1) contributory (i.e. has knowledge and understanding been extended by this research?), (2) defensible in design (i.e. exercise the researchers use an appropriate study design to address the research question posed?), (3) rigorous in bear (i.e. have the researchers been systematic and transparent in their collection, assay and estimation of the data?) and (4) credible in merits (i.e. are well-founded and plausible arguments offered?). Equally this tool does not have an overall rating category, three reviewers (SS, SM and SW) devised 1 consisting of three categories: (a) strong (80% or more of the quality indicators were met), (b) moderate (between 40 and 80% of the quality indicators were met) and (c) weak (less than 40% of the quality indicators were met).

To appraise the quality of the quantitative studies, the "Constructive Public Health Practice Project" (EPHPP) quality appraisal tool was used (Armijo-Olivo et al. 2012; Thomas et al. 2004). EPHPP is a 21-item checklist that highlights sources of bias including (1) choice bias, (2) study design, (3) confounders, (iv) blinding, (5) data collection methods, (6) withdrawal and dropouts and (seven) intervention integrity. The EPHPP tool also allocates a score of strong, moderate or weak rating, only it is of import to note that the scores applied are not equivalent across the two systems of criteria used to quality appraise the unlike studies (i.e. qualitative and quantitative).

The search also identified studies that employed a mixed-methods arroyo, using both quantitative and qualitative data. These were subjected to quality appraisal using both tools described to a higher place. The quality ratings for each study (strong, moderate, weak) are presented in the evidence tables (run into Supplementary Materials).

Data Extraction and Analysis

Data were extracted and findings organized based on (1) the type of report design employed, (ii) the populations included, (3) the blazon of MBI strategies delivered and (four) the outcomes assessed. This was washed in gild to assistance construct the narrative and compare between disparate interventions when considering effectiveness.

Results are presented according to the narrative synthesis method outlined by Petticrew and Roberts (2008), which allows findings from multiple studies to be summarized and explained past constructing the story (i.eastward. the narrative that emerges from reading, extracting from, quality appraising and reconsidering included studies). Petticrew and Roberts (2008) suggest that a narrative synthesis is generally best presented in words, the method besides allows for some statistical bear witness to be used in the construction of the narrative. Where possible, standardized consequence sizes (ESs) (Cohen's d) were calculates and categorized, every bit ES ≥ 0.2 = small, ES ≥ 0.5 = medium and ES ≥ 0.8 = large. For studies that did not nowadays data convertible to standardized effect sizes, p values were reported, wherever possible.

Results

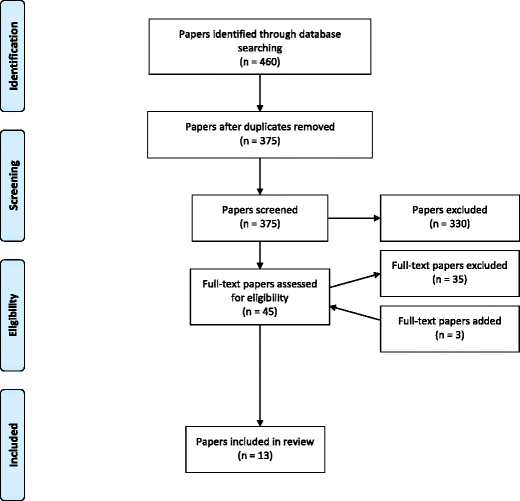

Following de-duplication, the main searches yielded 375 papers in total. After screening, 13 publications were included in the review (meet Fig. one). 11 were considered equally peer-reviewed journal publications, whilst two were not. One Indian study, published on the Vipassana Research Found website (http://www.vridhamma.org), was considered not to accept undergone contained peer review (Khurana and Dhar 2000), whilst another was an original PhD thesis and had not been published in a peer-reviewed periodical (Flinton 1998).

Menses diagram for paper screening results

Study Characteristics

Table i provides an overview of the studies included in the review. The majority of studies were carried out in the The states (12/13; 92%). One study was conducted in India. Three (23%) were RCTs, one (8%) was a controlled trial (CT), three (23%) used a pre-post study blueprint, three (23%) used a mixed-methods arroyo and iii (23%) used a qualitative report blueprint. I Indian study reported findings from a series of five disparate studies together, where different study designs had been used (CT or pre-post studies) in distinct populations. Where relevant, the results from each of these five studies are discussed. However, for convenience, this Indian study was placed in the "pre-post" category, every bit this was the method most commonly used.

Sample size varied markedly between studies, ranging from 27 (Himelstein et al. 2015) to 264 (Leonard et al. 2013) amongst the RCTs, with 42 (Flinton 1998) participants in the CT, 32 (Himelstein et al. 2012a) to 232 (Khurana and Dhar 2000) amongst the pre-post studies, 29 (Barnert et al. 2014) to 61 (Evans-Hunt 2015b) amid the mixed-methods studies and 10 (Himelstein et al. 2014) to 32 (Himelstein 2011) amongst the solely qualitative studies. Table two provides an overview of the study details, populations, intervention type and chief outcomes reported.

Populations, Compunction and Follow-Up

Twelve (92%) of the 13 studies focused on incarcerated young males. One study included both incarcerated young males and females. Beyond the studies, there were approximately 842 participants (verbal participant numbers in 1 study were unclear; Derezotes 2000). Of these 842 participants, 833 (99%) were male adolescents and ix (1%) were female person adolescents. Ages of the included participants varied, ranging from 14 to 23 years. Ethnicity was poorly characterized; where reported (n = half-dozen studies), almost participants were Black or Latino (98%) (Leonard et al. 2013), Latino (range 59–75%) (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein 2011; Himelstein et al. 2012a, 2015) or Hawaiian (60%) (Le & Proulx, 2015). About participants were housed in a juvenile correctional facility, with i facility being a community-based human service agency for adolescent sex offenders (see Tabular array ii).

Compunction was defined differently between studies, every bit either those participants who did non consummate the intervention or those participants who did not complete the upshot measures. Attrition rates for those who did not consummate the intervention varied, and only one-half of the quantitative studies reported these data (5/10; 50%) (see Tabular array 3). None of the included studies defined intervention completion. Overall, attrition from the intervention ranged from 8 to forty%, with a mean (SD) value of 22% (13.5). Intervention attrition percentages and reasons accounting for these are detailed in Table 3.

Three (30%) RCTs (Evans-Hunt 2015a; Himelstein et al. 2015; Leonard et al. 2013) provided details for compunction in terms of data collection. Attrition rates for those who did not complete consequence measures varied. Overall, attrition from information drove ranged from 25 to 56%, with a mean (SD) value of xl% (15.five). Data collection attrition percentages and reasons bookkeeping for these are detailed in Table 4.

Quality Appraisement

All of the quantitative studies had methodological limitations, including unclear recruitment techniques, minor sample sizes, high compunction rates, failure to control for of import confounders, use of non-validated measures and inconsistent reporting. Seven of the 10 papers that presented quantitative data were assigned a score of moderate, and 3 were assigned a weak score. None received a score of strong. Studies scored moderately on potential for blinding (9/10), report design (6/x), selection bias (5/x), confounders (5/10) and descriptions of withdrawal and dropout (5/10). The category where studies scored most strongly was data collection methods (7/10) (see Supplementary Materials). Quality scoring of the qualitative studies found scores of weak for ane written report and moderate for 5 studies. None of the qualitative studies were allocated a score of strong (encounter Supplementary Materials).

Interventions

The "Template for Intervention Description and Replication" (TIDieR) checklist and guide was referred to when extracting data nearly the interventions used in the included studies (Hoffmann et al. 2014). All interventions included at least two of the 3 cadre MBSR techniques (i.e. breath awareness, torso awareness and/or mindful movement). The interventions were characterized as heed trunk sensation (MBA), structured meditation program (SMP), Vipassana meditation (VM), cognitive behavioural therapy and mindfulness meditation (CBT/MM), mindfulness-based substance use (MBSU), Net-based mindfulness (IBM) and 1-to-one (1:i) mindfulness. See supplementary materials for a more than detailed description of the categorized interventions.

Interventions varied in terms of (1) setting, (ii) content, (3) dose and duration, (four) format, (5) teacher characteristics and (6) institutional constraints. In terms of setting, the quality and conditions of infinite provided varied widely, with some facilities being modified to suit the needs of the meditation course. For example, in one report, a Vipassana heart was set to create a "alive-in" meditation hall with areas for sleeping and eating (Khurana and Dhar 2000). Other courses were delivered in a less tailored setting (i.e. dormitories in which the immature men resided).

In terms of content, three interventions had a mindfulness-based curriculum specifically adapted for incarcerated immature men including psychotherapeutic topics relevant to their specific needs, mindfulness meditation, experiential activities and discussion fourth dimension (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein et al. 2012a, 2012b). One study was tailored towards drug rehabilitation (Himelstein 2011). Another written report merged mindful meditations with relaxation techniques—Jacobson's progressive muscle relaxation technique (Flinton 1998). 1 was heavily influenced by Buddhist teachings (Khurana and Dhar 2000). One study integrated social cognitive change components of CBT/MM (Leonard et al. 2013). One was delivered via the Cyberspace (Evans-Chase 2015b) and another on a 1-to-one basis, where mindfulness meditations were coupled with motivational interviewing, goal planning and preparatory work towards re-entry back into the customs (Himelstein et al. 2015).

Dose and duration ranged from one to ten h per session, being delivered daily over a flow of 10 days, or weekly over a period of 3 to 12 weeks (1–ii h daily). Some were delivered bi-weekly. One study included an intensive twenty-four hours parcel as an adjunct to the 10-calendar week class (Barnert et al. 2014). The VM course was delivered as an intensive silent retreat where participants spent upward to ten h per day in meditation and were provided with daily education on Buddhist philosophy, followed a vegetarian diet, and were separated from the rest of the incarcerated population and from social contacts. The mindfulness-based approaches were more secular by comparison and were instead integrated into daily prison routines, with classes taking identify weekly or bi-weekly, over 1 to ii h, more than closely adhering to the MBSR-type protocol.

Four studies did non include teacher characteristics (Barnert et al. 2014; Derezotes 2000; Flinton 1998; Khurana and Dhar 2000). Of those that did, details were generally vague. 1 study was delivered online using MP3 downloads, and the paper provided the name of the teacher and referred readers to his website (Evans-Hunt 2015b). But ane study provided details of the teachers' own meditation practices, which ranged from 5 to 30 years (Le & Proulx, 2015). Four courses were delivered by clinical psychologists, clinicians or social service workers who had both psychotherapeutic and meditation skills (Himelstein 2011; Himelstein et al. 2012a; Le & Proulx, 2015; Leonard et al. 2013). Simply ane written report referred to clinical supervision beingness provided (Leonard et al. 2013). The number of teachers delivering the courses varied. In one report, the author assumed the office of both researcher and instructor, raising the risk of researcher bias (Himelstein et al. 2012a).

Diverse authors noted that administrative, organizational and institutional constraints, such as shared cells and other restrictions of prison life, express full participation in the interventions. For example, space, privacy and racket constraints limited participants' power to do the meditation exercises in a number of settings. In some studies, resources were sparse or limited, with no provision of homework material immune. In one written report, recording of homework adherence was curtailed due to a fierce incident resulting in the confiscation of pens from all participants (Himelstein 2011).

Outcomes

Studies reported on a wide range of outcomes, mainly from self-report questionnaires. One study used an objective physiological measure (Le & Proulx, 2015), and 2 included behavioural measures (i.due east. behavioural regulation data collected via third person observations and ratings assigned by detention staff members) (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein et al. 2015). 1 study used a computerized attention network exam (ANT) to index attentional job performance (Leonard et al. 2013). No agin events were reported in any of the included studies.

Quantitative Outcome Findings

The total range of outcome assessments numbered 17 (see Supplementary Materials). For businesslike reasons, we have classified these as follows: self-regulation and emotional states (n = viii), mindfulness (n = v), mental health (anxiety and stress) (north = 4), problematic behaviour (impulsivity) (n = 3), QOL and wellbeing (n = two), substance use (n = 2) and criminal propensity (due north = 1). Follow-upwards generally took place immediately later the intervention simply. Ane report collected additional data at iv months post baseline (Leonard et al. 2013). The following section describes these outcomes in relation to the type of studies in which they were used.

Eight of the ten quantitative studies measured self-regulation and emotional states. Five reported pregnant improvements in emotional stability and self-regulation ability. These information are based upon iii RCTs (Evans-Chase 2013; Himelstein et al. 2015; Leonard et al. 2013), 1 CT (Flinton 1998) and four pre-post study designs (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein 2011; Himelstein et al. 2012a; Le & Proulx, 2015). 1 RCT (n = 61) found that older participants (ages xix–23) who received IBM scored higher on interpersonal self-restraint (Restraint-Weinberger Adjustment Inventory) compared to controls (p < 0.05) (Evans-Chase 2013). Another RCT (n = 147) reported a significantly lower degradation in performance on the ANT for those who had attended CBT/MM compared to the active control group (ES = 0.30, p < 0.01). For those in the CBT/MM group, functioning remained stable over fourth dimension among those who practised exterior of the educational activity sessions compared to those who did not (Leonard et al. 2013). Two studies examined prisoners' perception of control using the Prison Locus of Control Calibration (PLCS). In a small RCT (n = 27), Himelstein et al. (2015) reported no significant difference in the incarcerated young men'southward perception of control compared to the control group (ES = 0.25, p > 0.05) (Himelstein et al. 2015). In contrast, a small (north = 42) CT delivering SMP reported meaning improvements in participants' internal locus of control (ES = 1.47, p < 0.05) (Flinton 1998). Four pre-post studies (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein 2011; Himelstein et al. 2012a; Le & Proulx, 2015) delivering MBA reported contrasting results using the Salubrious Cocky-Regulation Scale (HRS) measure. Two studies (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein et al. 2012a) (n = 32 and n = 29) demonstrated a significant increment in cocky-regulation ability (ES = 0.44, p = 0.01; ES = 0.60, p < 0.01), whilst the other two (Himelstein 2011; Le & Proulx, 2015) (n = 48 and n = 33) reported no significant difference (ES = 0.25, p > 0.05; ES = 0.29, p > 0.05).

Five studies reported on levels of mindfulness following grooming. These included ii RCTs (Evans-Hunt 2015a; Himelstein et al. 2015), one CT (Barnert et al. 2014) and 2 pre-mail studies (Himelstein et al. 2012a; Le & Proulx, 2015). These studies delivered MBA (due north = 3), 1:i mindfulness and IBM. No pregnant changes were found.

Iii of four studies using mental wellbeing as an consequence reported benefit. A CT (due north = 42) delivering SMP reported significant reductions in measures of anxiety using the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (ES = i.14, p < 0.05), whilst 2 pre-post studies (due north = 32; northward = 33) delivering MBA reported significant reductions in levels of perceived stress (Perceived Stress Scale (PSS); ES = 0.42, p < 0.05; ES = 1.00, p < 0.05) (Himelstein et al. 2012a; Le & Proulx, 2015).

Quantitative measures of problematic behaviour were reported in three pre-post studies. All iii measured impulsiveness in incarcerated male adolescents using the Teen Conflict Survey (TCS). Himelstein (2011; n = 48) reported significant reductions post MBSU (ES = 0.43, p < 0.01). In contrast, Le and Proulx (2015; northward = 33) and Barnert et al. (2014; n = 29) reported no meaning changes in impulsivity among adolescents receiving MBA (ES = 0.32, p > 0.05; ES = 0.xx, p = 0.20). In addition, Himelstein et al. (2015) showed significantly lower infractions on behavioural points, as documented past juvenile detention centre officials.

Two of the ten quantitative studies reported on QOL. A RCT used the Rosenberg Cocky-Esteem Scale (RSE) and demonstrated significant improvements post i:1 mindfulness (ES = 0.60, p < 0.05) (Himelstein et al. 2015). A pre-postal service report demonstrated significant improvements in QOL (p < 0.01) using the Subjective Wellbeing Calibration (SWS) (Khurana and Dhar 2000).

Two of the ten studies reported on substance use. A pre-post study (n = 48) using the Monitoring the Future (MTF) questionnaire reported a significant increment in awareness of drug utilize take a chance among incarcerated male adolescents (ES = 0.75, p < 0.05) (Himelstein 2011). However, a RCT (n = 35) reported no significant difference on the MTF following 1:one mindfulness versus control (ES = 0.32, p > 0.05) (Himelstein et al., 2015).

Ane pre-post study reported on criminal propensity, finding a pregnant decrease in criminal propensity in adolescent males versus matched controls following VM training (p < 0.01) (Khurana and Dhar 2000).

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative findings are based on participants' commonage experience of a variety of different interventions: SMP, MBA, IBM and MBSU. Full general themes revolved around two key areas. The first was internal changes, such every bit participants feeling more relaxed, better able to manage stress, meliorate self-regulatory skills, improved self-awareness and being more optimistic about time to come prospects. The second related to external changes, such every bit improved relationships, valuing kindness shown by the teacher and being part of a supportive environs in which they felt respected and valued. Participants also reported feeling empowered by having met the challenge involved in adhering to the mindfulness practices. They appreciated being part of the group; developed more positive relationships with staff, peers and family; felt more in control; and were better able to cope with difficult feelings and impulses. They especially appreciated existence treated with care, respect and humaneness. In the principal, participants, family and staff were enthusiastic about and supportive of the courses. However, two studies highlighted small numbers of participants being resistant to the meditative practices (Barnert et al. 2014; Himelstein et al. 2015).

Discussion

This scoping review evaluated the existing bear witness for MBIs among young offenders. Information technology demonstrated that the existing international evidence regarding the utility of MBIs in youth offending populations is limited and the optimal arroyo unknown. Three RCTs, ane CT, three pre-post, three mixed-methods and three qualitative studies were included in the review. Pooled numbers produced an overall number of 842 participants, mainly male person (only ix/842 participants were female). Where reported, participant ages ranged from 14 to 23. In general, ethnicity was poorly characterized and the quality of methods was a limiting factor in almost all included studies. A wide range of MBIs was used, and thus, it was not possible to identify an optimal approach in terms of content, dose or intensity. Quantitative outcome measures were diverse, covering different aspects of mental wellness and wellbeing. Where applicable, upshot sizes ranged widely. From the six studies that nerveless qualitative data, unremarkably reported benefits revolved effectually two key areas: internal changes (such equally feeling less stressed, better able to manage difficult emotions) and external changes (such equally improved relationships). Three important hereafter considerations have been highlighted via the findings derived from this scoping review: (1) in that location is limited research regarding the use of MBIs amongst immature female offenders, (2) no significant changes were demonstrated in levels of mindfulness (in either direction) post-obit training and (3) there are multiple and circuitous challenges associated with researching MBIs within the prison house setting.

Findings from this scoping review resonate with those reported by Shonin et al. (2013) in a systematic review of Buddhist-derived interventions (BDIs) in correctional institutions. They reported recurrent bug with the quality of study methods, as did a more recent systematic review investigating yoga and meditation in offending populations (Auty et al. 2015). This current review found that three RCTs accept been conducted, only ii being of potent methodological quality, one of which was an unpublished PhD thesis, overlooked by all preexisting reviews. Shonin et al. (2013) reported only 2 RCTs, whereas Auty et al. (2015) institute four, but these were mixed with yoga interventions.

The electric current review demonstrated discrepancies in intervention delivery, content and outcomes, which makes it hard to draw meaningful comparisons betwixt interventions across studies. This is in keeping with Shonin et al. (2013), where meta-assay was deemed impossible due to the high levels of heterogeneity amongst interventions and outcome measures.

Future inquiry could potentially explore whether MBSR tin exist delivered in its standardized format or whether the intervention needs to exist adjusted to meet the specific needs and bug faced past young people who offend. Although meta-analysis was not possible in this scoping review, examination of discernable effect sizes suggests a wide range of potential effectiveness beyond various interventions and outcomes. This could imply that by practising the core components of mindfulness, young offenders may feel comeback in psychological and emotional wellbeing and in behavioural operation. Shonin et al. (2013) did not report effect sizes in their systematic review. However, Auty et al. (2015) did, demonstrating modest beneficial effects on psychological wellbeing (ES = 0.46) and behavioural performance (ES = 0.30). Auty et al. (2015) also showed that longer duration and less intense interventions were associated with larger effects.

Strengths and Limitations

The scoping review arroyo allowed a diversity of study methods to be assessed forth with cess of study quality, augmenting interpretation of results. Yet, for the qualitative studies, the research team applied a quality rating calibration that they devised themselves. Such an approach might obscure rather than enhance interpretation. For case, it does not consider "weighting" among the 18 assessment criteria where some markers of quality may be more than important than others. In addition, using two different appraisal methods makes information technology difficult to compare the relative value of quantitative studies compared to qualitative studies.

Publication bias is a major threat to the validity of any review. Therefore, obtaining and including information from unpublished trials is one fashion of addressing this bias. The possibility of non identifying relevant papers is a potential limitation. However, to counter this, a comprehensive search strategy was used, which included the gray literature (due east.m., one relevant unpublished PhD thesis was identified and included). In addition, only English studies were included, which may have resulted in the omission of relevant empirical findings.

The lack of a consensus definition of mindfulness is a source of ambiguity in clinical and research domains (Khoury et al. 2017). The current review sought to include studies defining MBIs in similar terms to Kabat-Zinn (i.eastward. including core components). Other interventions that describe upon mindfulness, such every bit acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) and dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT), were not included. These approaches, along with other related interventions (Yoga, Tai-Chi, pity-focused therapy, loving kindness meditation), may besides have a potential part in youth offending settings.

Inquiry Management and Implications for Practitioners

Young females are underrepresented in the research and feasibility of MBIs inside this population unclear. In this review, only i% of the populations studied were adolescent females. This may reverberate the low prevalence of females within the criminal justice system in general. Demographic figures from the Federal Agency of Prisons written report a 6.eight% prevalence of female offenders compared with a 93.ii% prevalence of male offenders (Federal Bureau of Prisons 2017). Data from the United kingdom suggests that female prisoners have a greater prevalence of mental wellness complaints, which might brand them more likely to seek out interventions. However, they are likewise reported to take unique needs when compared to male counterparts (less impulsivity and hostility; higher substance use and psychosis) rendering directly comparing a challenge (Birmingham 2003). Truthful prevalence of mental illness remains unknown in this context, and mental health concerns are likely to be undetected and untreated in offending populations as a whole (Birmingham 2003).

Now, comparison MBI studies amid young people who offend is challenging due to considerable heterogeneity in terms of study design, populations, interventions and issue measures used. In addition, mindfulness is potentially an ambiguous term, where a lack of a consensus definition, standardized intervention and/or specific outcome measure for mindfulness in this context makes it difficult to assess fidelity and effectiveness. What mindfulness means to young offenders, how it should be delivered and if it can address their complex needs remain to be convincingly established. Active MBI ingredients remain to exist subject to review (Crane et al. 2017; Gu et al. 2015), further compounding difficulties in creating the optimal approach for this particular population. Existing studies amongst youth offending populations accept by and large not recorded treatment adherence, a cardinal cistron in intervention effectiveness in other populations (Parsons et al. 2017). Therefore, although mindfulness is idea to be a key mediator of benign outcomes from MBIs (Alsubaie et al. 2017), measuring information technology as an outcome among youth offending populations is challenging.

A goal of future studies may be to establish agreed definitions and create standardized protocols (Crane et al. 2017; Dimidjian and Segal 2015). Such clarity could profoundly enhance interpretation of study findings, provide a standardized platform from which future researchers tin can build and ensure MBI teachers are appropriately trained and that the immature people are indeed receiving mindfulness training.

Using standardized outcome measures may also facilitate comparison. Hereafter controlled studies are required, ideally RCTs powered to detect definitive bear witness of effectiveness. Petty remains known well-nigh how these interventions compare with other ordinarily used psychological interventions, such equally CBT, or how cost-effective they might be.

Further high quality studies are needed if feasibility, effectiveness and implementability of these interventions are to be established. There is an urgent need for rigorous primary evaluations of mindfulness interventions for reducing factors known to increase the risk of re-offending, to develop this field and to guide future youth offending prevention programs and policies. In order to provide constructive, prove-based care for both male person and female young offenders, information technology is essential to conduct research with this population to reflect their particular circumstances and complex needs (Wakai et al. 2009). Yet, the challenge of conducting rigorous enquiry within a prison setting must also be acknowledged and accommodated for in future research in this area.

Researchers working in this setting need to anticipate potential organizational and/or logistical issues that may delay or disrupt the research process (Byrne 2017), for example background checks, compulsory training and seeking permission to bring research materials onsite (Wakai et al. 2009). Retaining research participants is a business organisation for all researchers, just incarcerated populations have an exceptionally high compunction charge per unit for a number of reasons (east.g., transfer, release, participants on remand, courtroom appearance, medical visits, family visits, administrative segregation), which can ofttimes be unanticipated (Byrne 2017; Shonin et al. 2013; Wakai et al. 2009). Researcher need to work collaboratively with prison staff and program well in advance then that necessary procedures can be put in place to minimize the burden to prison house staff and movement of the immature offenders. Developing constructive interventions to serve this population is paramount, and enquiry approaches need to be responsive to the challenges faced in this type of setting besides every bit gaining a ameliorate understanding equally to what these young people need. Therefore, there is a demand for mixed-methods research designs, especially if RCTs are not implementable in real-life settings.

References

-

Abram, K. Yard., Teplin, L. A., Charles, D. R., Longworth, Southward. L., McClelland, G. M., & Dulcan, M. K. (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder and trauma in youth in juvenile detention. Archives of Full general Psychiatry, 61, 403–410. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.four.403

-

Alsubaie, M., Abbott, R., Dunn, B., Dickens, C., Keil, T., Henley, W., & Kuyken, W. (2017). Mechanisms of action in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in people with physical and/or psychological conditions: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 55(Supplement C), 74–91. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.cpr.2017.04.008

-

Andrews, D. A., Bonta, J., & Hoge, R. D. (1990). Classification for effective rehabilitation: Rediscovering psychology. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 17, 19–52. https://doi.org/x.1177/0093854890017001004

-

Armijo-Olivo, S., Stiles, C. R., Hagen, N. A., Biondo, P. D., & Cummings, Thou. Chiliad. (2012). Cess of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparing of the Cochrane collaboration risk of bias tool and the effective public wellness practice project quality assessment tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18, 12–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01516.x

-

Arnsten, A. F. T. (1999). Evolution of the cognitive cortex: XIV. Stress impairs prefrontal cortical role. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38, 220–222. https://doi.org/ten.1097/00004583-199902000-00024

-

Arskey, H., & Malley, 50. O. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Enquiry Methodology, 8(one), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

-

Auty, K. Thousand., Cope, A., & Liebling, A. (2015). A systematic review and meta-analysis of yoga and mindfulness meditation in prison: Effects on psychological well-being and behavioural performance. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 61(half-dozen), 689–710. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X15602514

-

Baer, R. A. (2003). Mindfulness grooming as a clinical intervention: A conceptual and empirical review. Clinical Psychology: Scientific discipline and Practice, 10(2), 125–143.

-

Barnert, E. S., Himelstein, S., Herbert, S., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Chamberlain, L. J. (2014). Exploring an intensive meditation intervention for incarcerated youth. Kid & Adolescent Mental Wellness, xix(one), 69–73. https://doi.org/x.1111/camh.12019

-

Birmingham, L. (2003). The mental wellness of prisoners. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 9(iii), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.9.3.191

-

Bohlmeijer, Eastward., Prenger, R., Taal, Due east., & Cuijpers, P. (2010). The furnishings of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental wellness of adults with a chronic medical disease: A meta-assay. Journal of Psychosomatic Inquiry, 68(half dozen), 539–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2009.10.005

-

Byrne, Southward. (2017). The development and evaluation of a mindfulness-based intervention for incarcerated young men. PhD thesis. University of Glasgow. Retrieved from http://encore.lib.gla.ac.uk/iii/encore/record/C__Rb3269060.

-

Cerqueira, J. J., Mailliet, F., Almeida, O. F. X., Jay, T. M., & Sousa, N. (2007). The prefrontal cortex as a cardinal target of the maladaptive response to stress. Journal of Neuroscience, 27(11), 2781–2787. https://doi.org/x.1523/JNEUROSCI.4372-06.2007

-

Chiesa, A., & Serretti, A. (2009). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: A review and meta-analysis. Journal of Culling and Complementary Medicine, fifteen(5), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2008.0495

-

Chitsabesan, P., Kroll, L., Bailey, South. U. E., Kenning, C., Sneider, S., MacDonald, West., & Theodosiou, L. (2006). Mental wellness needs of young offenders in custody and in the customs. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(6), 534–540. https://doi.org/x.1192/bjp.bp.105.010116.

-

Crane, R. S., Brewer, J., Feldman, C., Kabat-Zinn, J., Santorelli, S., Williams, J. M. Yard., & Kuyken, Due west. (2017). What defines mindfulness-based programs? The warp and the weft. Psychological Medicine, 47(6), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716003317

-

Daudt, H. Yard., van Mossel, C., & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: a large, inter-professional squad's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 48. https://doi.org/x.1186/1471-2288-xiii-48.

-

DeBellis, M. D., & Thomas, L. (2003). Biologic findings of post-traumatic stress disorder and child maltreatment. Current Psychiatry Reports., 5, 108–117. https://doi.org/ten.1007/s11920-003-0027-z

-

Derezotes, D. (2000). Evaluation of yoga and meditation trainings with adolescent sex offenders. Kid and Adolescent Social Piece of work Journal, 17(ii), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007506206353

-

Dimidjian, Southward., & Segal, Z. V. (2015). Prospects for a clinical scientific discipline of mindfulness-based intervention. American Psychologist, seventy(7), 593–620. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039589

-

Dodge, K. A., & Pettit, Grand. S. (2003). A biopsychosocial model of the development of chronic deport problems in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 39(2), 349–371.

-

Duckworth, A. Fifty., Kim, B., & Tsukayama, E. (2013). Life stress impairs cocky-command in early adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, three, one–12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00608

-

Evans-Hunt, Chiliad. (2013). Internet-based mindfulness meditation and self-regulation: A randomized trial with juvenile justice involved youth. OJJDP Journal of Juvenile Justice, iii, 63–79.

-

Evans-Hunt, M. (2015a). Mindfulness meditation with incarcerated youth: A randomized controlled trial informed by neuropsychosocial theories of boyhood. International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 47, 3–three. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2015.04.018

-

Evans-Chase, Chiliad. (2015b). A mixed-methods examination of Net-based mindfulness meditation with incarcerated youth. Advances in Social Piece of work, sixteen, 90–106.

-

Farrington, D. (2000). Psychosocial predictors of developed antisocial personality and adult convictions. Behavioural Science and the Law, eighteen, 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-0798(200010)eighteen:v<605::Aid-BSL406>3.0.CO;2-0

-

Fazel, Southward., Helen, D., & Niklas, 50. (2008). Mental disorders among adolescents in juvenile detention and correctional facilities: a systematic review and metaregression analysis of 25 surveys. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 47(9), 1010–1019. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.ObO13e31817eecf3.

-

Federal Agency of Prisons. (2017). Inmates gender. Open Government. Retrieved from https://world wide web.gov/about/stastics_inmat_gender.jsp.

-

Fjorback, Fifty., Arendt, M., Ørnbøl, Eastward., Fink, P., & Walach, H. (2011). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy—A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124(2), 102–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01704.ten

-

Flinton, C. A. (1998). The effects of meditation techniques on feet and locus of control in juvenile delinquents. Dissertation: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering science (59), ProQuest Information & Learning, US. Retrieved from EBSCOhost psyh database.

-

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, North. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., … Shihab, H. M. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/x.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018.

-

Grossman, P., Niemann, Fifty., Schmidt, S., & Walach, H. (2004). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits. A meta-analysis. Periodical of Psychosomatic Inquiry, 57(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(03)00573-seven

-

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cerebral therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction meliorate mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, i–12. https://doi.org/x.1016/j.cpr.2015.01.006

-

Himelstein, Southward. (2011). Mindfulness-based substance abuse handling for incarated youth: A mixed method pilot report. International Journal of Transpersonal Studies, thirty, 1), 2–1),10.

-

Himelstein, South., Hastings, A., Shapiro, Due south., & Heery, Yard. (2012a). Mindfulness grooming for cocky-regulation and stress with incarcerated youth. A pilot report. Probation Journal, 59(2), 151–165. https://doi.org/ten.1177/0264550512438256

-

Himelstein, South., Hastings, A., Shapiro, S., & Heery, Yard. (2012b). A qualitative investigation of the experience of a mindfulness-based intervention with incarcerated adolescents. Kid and Boyish Mental Wellness, 17(4), 231–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2011.00647.ten

-

Himelstein, S., Saul, S., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Pinedo, D. (2014). Mindfulness training every bit an intervention for substance user incarcerated adolescents: A pilot grounded theory study. Substance Use & Misuse, 49(five), 560–570. https://doi.org/x.3109/10826084.2013.852580

-

Himelstein, S., Saul, Due south., & Garcia-Romeu, A. (2015). Does mindfulness meditation increase effectiveness of substance abuse treatment with incarcerated youth? A pilot randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1472–1480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0431-6

-

Hoffmann, T. C., Glasziou, P. P., Boutron, I., Milne, R., Perera, R., Moher, D., … Michie, S. (2014). Better reporting of interventions: Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 348. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g1687.

-

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and low: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018555

-

Hölzel, B. M., Lazar, S. Due west., Gard, T., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Vago, D. R., & Ott, U. (2011). How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, half dozen(6), 537–559. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611419671

-

Khoury, B., Knäuper, B., Pagnini, F., Trent, N., Chiesa, A., & Carrière, K. (2017). Embodied mindfulness. Mindfulness, viii(5), 1160–1171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0700-vii

-

Khurana, A., & Dhar, P. L. (2000). Effect of Vipassana meditation on quality of life, subjective well-being, and criminal propensity among inmates of Tihar jail, Delhi. Retrieved from http://world wide web.vri.dhamma.org.

-

Kuyken, W., Byford, S., Taylor, R. S., Watkins, East., Holden, E., White, K., … Teasdale, J. D. (2008). Mindfulness-based cerebral therapy to prevent relapse in recurrent depression. Periodical of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(half dozen), 966–978. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013786.

-

Kuyken, Westward., Hayes, R., Barrett, B., Byng, R., Dalgleish, T., Kessler, D., … Cardy, J. (2015). Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of mindfulness-based cerebral therapy compared with maintenance antidepressant handling in the prevention of depressive relapse or recurrence (Foreclose): A randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 386(9988), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)62222-4.

-

Lao, S.-A., Kissane, D., & Meadows, G. (2016). Cerebral effects of MBSR/MBCT: A systematic review of neuropsychological outcomes. Consciousness and Cognition, 45, 109–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2016.08.017

-

Le, T. N., & Proulx, J. (2005). Feasibility of mindfulness-based intervention for incarcerated mixed-ethnic native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander youth. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(ii), 181–189. https://doi.org/x.1037/aap0000019

-

Leonard, Northward., Jha, A., Casarjian, B., Goolsarran, Chiliad., Garcia, C., Cleland, C., … Massey, Z. (2013). Mindfulness training improves attentional chore performance in incarcerated youth: A grouping randomized controlled intervention trial. Frontiers in Psychology, four, 792. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00792.

-

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, Chiliad. (2010). Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implementation Scientific discipline, five(69), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

-

Lipsey, M. (1995). What do we learn from 400 research studies on the effectiveness of treatment with juvenile delinquents? In J. McGuire (Ed.), Wiley series in offender rehabilitation. What works: Reducing reoffending: Guidelines from enquiry and exercise (pp. 63–78). Oxford: John Wiley.

-

Loeber, R., Farrington, D. P., & Petechuk, D. (2013). Bulletin 1: From juvenile delinquency to young adult offending. Washington, DC: Department of Justice.

-

Lösel, F. (1995). Increasing consensus in the evaluation of offender rehabilitation? Lessons from contempo inquiry syntheses. Psychology, Criminal offense & Law, 2, 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169508409762

-

Marmot, K. (2005). Social determinants of wellness inequalities. The Lancet, 365(9464), 1099–1104. https://doi.org/ten.1016/s0140-6736(05)71146-half dozen

-

Mars, T. South., & Abbey, H. (2010). Mindfulness meditation practice as a healthcare intervention: A systematic review. International Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, 13(2), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijosm.2009.07.005

-

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., & Mulvey, E. P. (2009). Trajectories of antisocial beliefs and psychosocial maturity from adolescence to young adulthood. Developmental Psychology, 45(vi), 1654–1668. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015862

-

Monahan, K. C., Steinberg, 50., Cauffman, E., & Mulvey, E. P. (2013). Psychosocial (im) maturity from adolescence to early adulthood: Distinguishing between adolescence-express and persisting hating behavior. Evolution and Psychopathology, 25(4pt1), 1093–1105. https://doi.org/x.1017/s0954579413000394

-

Ou, S.-R., & Reynolds, A. J. (2010). Childhood predictors of immature adult male crime. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(8), 1097–1107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.02.009

-

Parsons, C. Due east., Crane, C., Parsons, L. J., Fjorback, 50. O., & Kuyken, W. (2017). Home practice in mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of participants' mindfulness practice and its association with outcomes. Behaviour Inquiry and Therapy, 95, 29–41. https://doi.org/ten.1016/j.deviling.2017.05.004

-

Petticrew, K., & Roberts, H. (2008). Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. New York: John Wiley.

-

Rothbart, M. K. (2007). Temperament, evolution, and personality. Electric current Directions in Psychological Science, xvi(4), 207–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00505.10

-

Rothbart, M. G., Sheese, B. E., & Posner, M. I. (2007). Executive attention and effortful control: Linking temperament, encephalon networks, and genes. Child Development Perspectives, 1, 2–vii. https://doi.org/x.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00002.x

-

Sapouna, Bisset, C., & Conlong, A. Chiliad. (2011). What works to reduce reoffending: A summary of the evidence justice analytical services Scottish government. Retrieved from http://www.huckfield.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/xi/eleven-SG-What-Works-to-Reduce-Reoffending-Oct1.pdf.

-

Shonin, East., Van Gordon, W., Slade, Yard., & Griffiths, M. D. (2013). Mindfulness and other Buddhist-derived interventions in correctional settings: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Beliefs, 18(3), 365–372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2013.01.002

-

Spencer, Fifty., Ritchie, J., Lewis, J., & Dillon, L. (2003). Quality in qualitative evaluation: a framework for assessing inquiry evidence. Cabinet Role: National Centre for Social Research.

-

Steinberg, L. (2007). Adventure taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(ii), 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00475.10

-

Steinberg, L., Albert, D., Cauffman, E., Banich, G., Graham, Southward., & Woolard, J. (2008). Age differences in awareness seeking and impulsivity every bit indexed past behavior and cocky-report: Evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology, 44(six), 1764–1778. https://doi.org/ten.1037/a0012955

-

Steinberg, Fifty., Cauffman, E., Woolard, J., Graham, S., & Banich, M. (2009). Are adolescents less mature than adults?: Minors' access to abortion, the juvenile death penalty, and the alleged APA "flip-flop". American Psychologist, 64(7), 583–594. https://doi.org/ten.1037/a0014763

-

Teasdale, J. D., Moore, R. Thousand., Hayhurst, H., Pope, M., Williams, S., & Segal, Z. V. (2002). Metacognitive awareness and prevention of relapse in low: Empirical evidence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(2), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.seventy.2.275

-

Thomas, B. H., Ciliska, D., Dobbins, M., & Micucci, S. (2004). A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public wellness nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 1(iii), 176–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x

-

Vitacco, M. J., Neumann, C. Southward., & Caldwell, Thousand. F. (2010). Predicting antisocial behavior in loftier-risk male adolescents: Contributions of psychopathy and instrumental violence. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(8), 833–846. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854810371358.

-

Vitacco, Thousand. J., Neumann, C. Due south., Robertson, A. A., & Durrant, S. 50. (2002). Contributions of impulsivity and callousness in the cess of adjudicated male person adolescents: A prospective report. Journal of Personality Cess, 78(1), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327752jpa7801_06.

-

Wakai, S., Shelton, D., Trestman, R. L., & Kesten, K. (2009). Conducting research in corrections: Challenges and solutions. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 27(v), 743–752. https://doi.org/x.1002/bsl.894

-

Ward, T., Yates, P. Yard., & Willis, G. Chiliad. (2012). The good lives model and the risk demand responsivity model. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(1), 94–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811426085

-

Wilson, R. J., & Yates, P. Thousand. (2009). Effective interventions and the adept lives model: Maximizing treatment gains for sexual offenders. Assailment and Violent Behavior, 14(3), 157–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.01.007

-

Witkiewitz, Marlatt, G. A., & Walker, D. (2005). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance employ disorders. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, xix(iii), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1891/JCOP.2005.19.3.211

-

Witkiewitz, Bowen, Douglas, & Hsu. (2013). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for substance craving. Addictive Behaviors, 38(2), 1563–1571. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.04.001

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open up Admission This article is distributed under the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted utilize, distribution, and reproduction in whatsoever medium, provided you give advisable credit to the original writer(due south) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simpson, S., Mercer, Southward., Simpson, R. et al. Mindfulness-Based Interventions for Young Offenders: a Scoping Review. Mindfulness 9, 1330–1343 (2018). https://doi.org/ten.1007/s12671-018-0892-five

-

Published:

-

Issue Date:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0892-5

Keywords

- Incarcerated

- Mindfulness

- Meditation

- Offending

- Scoping review

Source: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12671-018-0892-5

0 Response to "Literature Review on Intervention Methods for Youth Offenders"

Post a Comment